By Eric Hammel

Dwight David Eisenhower began life as David Dwight Eisenhower in Abilene, Kansas, on October 14, 1890, the third of five sons. It is known that his given names were rearranged because he was named David after his father and that his mother called him Dwight to avoid confusion. The rearrangement became permanent and, at some point, legal. His schoolmates called him “Ike,” and that is the name that really stuck; no last name is ever needed when mention of him comes up, just plain Ike does the job.

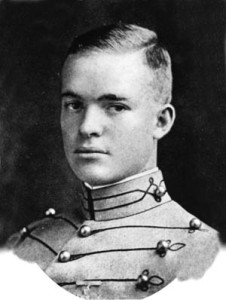

A Cadet at West Point

Raised in humble circumstances within miles of the geographical and geodetic centers of the vast United States, Ike naturally focused his ambitions on a career in the Navy, sought an appointment to the United States Naval Academy as one in a long, long line of seekers after an excellent free college education. To help the two elder of his four brothers get started in college, as well as help feed the entire family, Ike put off his own dreams for a few years to simply earn money. Indeed, by the time he got around to seeking an appointment to Annapolis in 1910, he had slipped beyond the maximum age for a new cadet. He had to settle for his free education at the United States Military Academy at West Point. He was appointed a cadet in 1911 and began as a brand new one on June 14 of that year.

photographed in June 1915.

As in high school, Ike was a so-so student, apt to expend most of his energy in study he liked and very little in all else. Some of his professors considered him very bright, others less so. He excelled at football, however, in such an excessive manner that he would have been remembered solely for his game had history not fallen on his shoulders. He suffered an injury to his knee that ended his playing days and nearly cost him his free education. He learned and suffered conformity enough to keep his standing as a cadet, but he also evidenced a brilliant mind for the practical joke.

Cadet Eisenhower was awarded his commission in the infantry in June 1915, having graduated 61st of 164. His class, more than any other, would be touched by History, would be known in due course as the Class the Stars Fell On. Two of its members would be among only five U.S. Army officers ever to wear five stars.

Ike Misses the First World War

Second Lieutenant Eisenhower’s first posting was to the 19th Infantry Regiment as Fort Sam Houston, in the back lot of San Antonio, Texas. There, in addition to coaching the football team at a local military academy, Ike met and courted Mamie Doud. The couple became engaged on February 14, 1916, Valentine’s Day, and they were married on July 1. Ike thought of taking up flying, but in the brief months between engagement and marriage his future in-laws had firmly laid down the law: If he took up flying, he must give up Mamie. Ike struggled with the choice. During the four-day period when this crisis came to a head, he opted for Mamie and thus found himself ready to buckle down and excel at his career as an infantry officer. He later wrote, “The decision was to perform every duty given me in the Army to the best of my ability and to do the best I could to make a creditable record, no matter what the nature of the duty.” The test of this credo came soon enough.

In April 1917, as the nation girded for entry into World War I, Ike was temporarily drawn into training an Illinois National Guard regiment, then transferred to help form the new 57th Infantry Regiment. He was promoted permanent captain in May 1917. After only six months, Captain Eisenhower was dispatched to Georgia to train officer candidates in fieldcraft. And in two more months he washed up at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to lead a company of officer candidates and oversee physical training for an entire training regiment. Mamie, who gave birth to a son, christened David Dwight, remained at Fort Sam Houston.

Naturally, Ike bombarded the Army with missives offering his life in return for combat duty in France. Why not; most of his West Point classmates were there or preparing to ship out. The Army responded in February 1918 with a transfer to Fort Meade, Maryland, to join an engineer regiment that was preparing a heavy tank battalion for duty in France. In March, Ike was told he would command the tank battalion at the front, but shortly he was ordered to lead everyone who was not going to France to Camp Colt, near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in order to build a brand-new tank battalion from scratch. Ike was the only Regular Army officer assigned to the new base.

At Camp Colt, the troops commanded by Ike were designated the nucleus of the new Army Tank Corps and assigned the mission of training all of the Army’s replacement tank crewmen, who would graduate to the war. But even that went awry. Thanks to an arcane agreement with the British, the trained tank men were marooned at Camp Colt; none of them went to France, yet Ike’s trainers kept churning out new ones. Made a temporary major in June 1918, Ike tried to put on a cheerful face and an enthusiastic demeanor. On the inside, nevertheless, he seethingly contemplated resigning his commission as soon as hostilities ended.

Things began to look up for Ike on his 28th birthday, October 14, 1918, when he received advance news that he was to be promoted lieutenant colonel and, even better, received orders to France with his trained tank crews. Departure was set for November 18. He next turned down an offer of promotion to colonel if he agreed to remain at Camp Colt, but the whole uptick in fortunes was shot through the heart on November 11, when the Armistice was signed in France.

Ike remained a lieutenant colonel until the summer of 1920, when he was reduced back to his substantive rank, captain. But he was promoted permanent major in December with a June 1920 date of rank. Many a wartime lieutenant colonel—the 10-years-older George Marshall among them—received identical treatment (lieutenant colonel to captain to major), so Ike knew that he was going to be a major for a very long time. As things turned out, it was to be 16 years.

Meeting Patton

Ike remained in the Tank Corps following the Armistice and served at several bases until the corps was consolidated at Fort Meade under the new Infantry Tank School. Here he met and fell into the orbit of Colonel (but soon enough Major) George Patton, a cavalryman who had served colorfully at the head of a tank brigade in World War I. The two became fast friends and partners in applying lessons learned to the nascent American tank doctrine. Patton was five years older than Ike and had graduated from West Point six years ahead of Ike, but the two became inseparable friends and partners. Patton’s worldview led him to posit independent divisions formed upon a backbone of fast, well-armed tanks, while Ike’s led him to lobby for inclusion of tank units in the standard infantry division. Neither agenda progressed all that far while they served at Fort Meade, but they and the American armies in Europe wielded exactly such weapons 20 years hence.

It was the friendship with Patton that led Ike to his first brush with greatness. Neighbors as well as colleagues and friends, the two socialized regularly. One day in 1919, Patton invited Ike to his home to meet Brig. Gen. Fox Conner, a renowned military genius who had served as chief of operations at Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force (AEF) headquarters in France (where, incidentally, Conner had mentored his subordinate, Colonel George Marshall). When he met Ike, Conner was Pershing’s chief of staff at AEF headquarters in Washington.

Conner and the Canal

Conner, who was known for his ability and keen desire to be exposed to new ideas, had a splendid and useful evening with the odd couple of Patton and Eisenhower, and he marked the younger down as a man to see to. Conner ended 1921 in command of an infantry brigade in the Panama Canal Zone, and he invited newly demoted Major Eisenhower to serve as his executive officer. The invitation was a godsend; a few days after Christmas 1920, three-year-old David Dwight was dead from scarlet fever and the distraught Eisenhowers needed to start over somewhere else.

Conner’s brigade had been stripped of one of its two infantry regiments and, for all its strategic importance, the Canal Zone was something of a military backwater. Ike’s official duties were light, giving him plenty of reason to leap at every opportunity to keep his mind active. It was in this atmosphere that Fox Conner, one of the great military minds of his era, began his three-year effort to inscribe all he knew and all he believed on the mind of a man he felt might be one of the next generation’s great military leaders. Conner assigned books for Ike to read—a roiling broth of history, poetry, fiction, military doctrine, and philosophy—then Ike sat with his mentor to discuss every aspect of the current volume from every angle either could think of. The two also relived every major military campaign in history by means of maps and text and milked every imaginable lesson for modern warfare from each of them. Conner, in his role as military oracle, repeatedly impressed upon Ike that the next war was going to bring the United States into a coalition, no doubt with Britain, and that coalition warfare was the most difficult to manage. Engraved on Ike’s soul—and thus on history—were Conner’s three interlinked maxims: Never fight unless you have to, never fight alone, and never fight for long.

Conner thus readied Ike for the job Ike, above all other Americans of his generation, would be best equipped to master and lead. Ike later wrote of his three-year sojourn as Conner’s single acolyte: “[Life with Conner] was a sort of graduate school in military affairs and the humanities, leavened by comments and discourses of a man who was experienced in his knowledge of men and their conduct.”

While living in the Canal Zone, and thanks in large measure to subtle conditioning of Mamie by Mrs. Conner, the Eisenhowers managed to clear the air between themselves over David’s death and get on with raising John, who was born in the summer of 1922.

Ike in Academia

The Infantry Tank School reclaimed Ike in September 1924—to coach the base football team—but Ike went straight to work to earn a student billet at The Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. This fair fruit was denied the football coach, but Fox Conner, from his new position as deputy chief of staff of the Army, pulled a series of strings in the background that yielded, in August 1925, a coveted place for Ike as student at the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The pace at Leavenworth was much more grueling that the pace on post under Fox Conner, but for Ike it was mostly a repeat course. He studied hard and graduated at the top of his class, a really important career milestone, especially for a man who had missed his generation’s big war. Moreover, the friendships Ike forged or renewed at Leavenworth would be invaluable in the future. More to the point, the Leavenworth experience and its laudatory outcome finally ignited in Ike a fierce fire that caused him to aspire to greatness. Even Ike admitted to its being a “watershed in my life.”

From Kansas, the Eisenhowers were ordered to Fort Benning, where Ike, who had been reassigned to the infantry branch, was to serve as executive officer—and football coach—for The Infantry School’s crack demonstration infantry regiment. When Fox Conner learned of this, he once again used his high office in Ike’s behalf and had the 37-year-old major reassigned to duty in Washington, D.C., at the Battle Monuments Commission, which was headed by retired General of the Armies John J. Pershing. When Ike wrote (with help from his youngest brother, Milton, a former journalist, now an assistant secretary of agriculture) a guidebook for the effort, Pershing judged it excellent and wrote a commendatory letter for the major’s personnel file.

Ike next requested assignment as a student at the Army War College, which offered advanced military education at a much more leisurely pace than Leavenworth. Here, again, Ike came in daily contact, at work and play, with the best soldiers of his generation.

Upon graduation from the War College in June 1928, Ike accepted an offer to return to the Battle Monuments Commission on the promise that he would be able to spend a year in France. This seeming junket proved to be a valuable investment by the American nation. As Ike traversed most of France in a chauffeur-driven car, the military part of his mind idly fought mock campaigns on the passing vistas, memorizing terrain as it did. Who could know the benefits derived from Ike’s memories of these days and weeks on the road?

Drafting the Industrial Mobilization Plan

The one-year sojourn in France led to a return to Washington, where in November 1929, Major Eisenhower became one of two assistant executive officers assigned to the assistant secretary of war. The enterprise Ike had joined was the primary node of an effort to catalogue the whole of American industry against a time in which it might be mobilized to support an all-out war effort. The task had come about as a result of the monumentally lousy job industry and the military had done in modulating needs and effort for World War I. Ike and his fellow assistant, an engineer major, did the heavy lifting, and once again a future United States benefited immensely from the effort. Major Eisenhower lived for a time at the exact nexus between the military and the industrial behemoth that would supply, equip, and feed it in time of war—if all went well and the new economic depression didn’t obliterate one or both sides of the crucial equation.

Ike’s tenure at the office of the assistant secretary of war coincided with important planning events. The Army’s duty to maintain readiness for war had been enshrined in the National Defense Act of 1920, a document whose genesis had been overseen by Fox Conner under Pershing’s command. The army’s own document covering that ground was the Protective Mobilization Plan. But this plan covered only the Army, not the American industrial base that was needed to bring the plan to fruition on battlefields. The Army required such a plan—an industrial mobilization plan. The office of the assistant secretary had jurisdiction, and Ike and his fellow assistant executive officer were tasked with writing at least an outline.

The immediate result came in the form of long journeys to confer upon a parochially educated Army officer all he needed to know about the inner workings of his nation’s industrial base. By undertaking the educational requirements of the task, Ike came face to face with what was possible—and not possible—for industry to do for an army. This was a private education fit for a future commander in chief of a war effort born in its largest degree upon the potentials of industry and how they might be directed in such a way as to literally overwhelm an enemy state. To start with, Ike studied all that had gone wrong with the lamented 1915–1920 industrial mobilization, and he did so with aid of many of the lions of American industry, such as Bernard Baruch, and the heads of American Telephone and Telegraph, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and other corporate giants. Along the way, he received an education in constitutional restraints on how the government might deal with private wealth and power in a future national emergency. It was, all told, one hell of an eye-opening experience for an obscure mid-ranked officer from the dusty Kansas prairie.

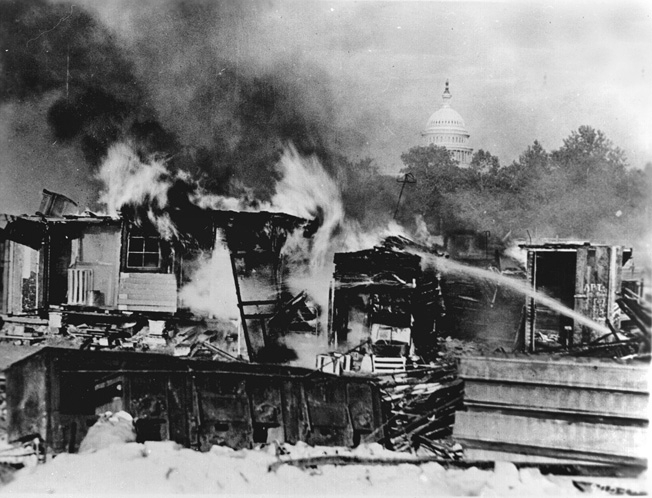

MacArthur Routs the Bonus March

By the time the industrial mobilization plan had been drafted, General Douglas MacArthur had become Army chief of staff (having stepped up to it over Fox Conner’s head in 1930). The heart of the plan, once outlined to the requisite government authorities, brought Ike to MacArthur’s attention and slowly into his orbit. When Ike’s immediate boss moved over from the office of the assistant secretary to become deputy chief of staff (and thus overseer of the Army’s budget), Ike remained formally assigned as assistant to the new executive but was increasingly called on to serve as an informal aide-de-camp to MacArthur. He was thus at MacArthur’s side during one of the sorriest episodes in U.S. Army history, the July 1928 military riot that dispersed down-and-out World War I veterans who had rallied to Washington, D.C., to seek a government bonus for their war service.

The so-called Bonus March looked like a nascent Bolshevik revolution to conservative Army officers, Ike among them. MacArthur simply went hog wild when he was deputized by President Herbert Hoover to disperse these luckless former comrades seeking redress from their nation, which once upon a time had declared itself grateful for their sacrifices in war.

Though highly disciplined (it was supervised by a retired general), the so-called Bonus Expeditionary Force refused to vacate several government sites in the capital district after a bill seeking the bonus was voted down in both houses of Congress. This refusal to disperse triggered an order from President Hoover for General MacArthur to quell what Hoover characterized as a riot. The bonus marchers were in illegal possession of government land, mainly owned by the Department of the Treasury, but they were peaceful, even passive.

With a squeamish and unhappy Ike at his side, a beautifully uniformed MacArthur unleashed infantry and mounted cavalry (the latter commanded by George Patton) to clear the marchers from the occupied grounds. In the heat of “battle” the chief of staff apparently—allegedly—ordered some of his troops to destroy the squalid bonus encampments near Anacostia by fire in retaliation for allegedly hurled bricks and other debris. Ike hated and even feared the revolutionary potential of the Bonus March, but he nonetheless hated to see the ragged former soldiers burned out.

FDR’s New Deal

That November, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president by an overwhelming margin, and he and his New Deal blew into Washington in March 1933. By then, Ike had been formally assigned as MacArthur’s aide-de-camp and, wonder of wonders, MacArthur was retained by the new president. In short order, Ike was pulled into preparing the Army for overseeing the start-up of the new Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), an effort to put tens and hundreds of thousands of jobless youths to work cleaning lakes and streams, planting what would come to be billions of trees, and generally sprucing up federal parks and preserves. The Army, tasked with organizing, leading, and victualing the CCC, benefited immensely from an exercise almost identical to a military mobilization and shooting-free military expedition. Nearly at the center of the effort was Ike, who like Marshall (and Hap Arnold), gained immensely important insights into executive oversight of the art and science of manpower mobilization and maintaining a massive and far-flung military campaign in the field.

As to the rest of the New Deal, it drove professional soldiers crazy. Ike was not immune to detesting it even though, in the end, it brought the nation most of the way out of the Great Depression and set the stage for the unbeatable industrial mobilization of 1938–1945 that undergirded Ike’s own rise to undreamable heights.

Following MacArthur to the Philippines

MacArthur’s term as chief of staff ended in 1935. Though MacArthur formally retired from the U.S. Army, he was hired by the president-elect of the soon-to-be-independent Philippines, Manuel Quezon, to oversee the creation of a Philippine defense force. As such, MacArthur remained in some shadowy active-duty status and was allowed to take several active-duty field-grade officers with him. His first choice was Ike, who was a bit torn by the offer. His chief imperative at that stage of his career was to command troops, something he had done very little of in the 20 years since he left West Point. But there was no way he could turn his back on the important, even historical, work—not to mention the adventure—MacArthur’s offer was bound to lead to. Besides, here was an opportunity to put much of his theoretical army-building experience to practical use.

Ike arrived in Manila—bachelor for a year—in September 1935. The task at hand was to build a conscript army from meager financial allotments and obsolete weapons sufficient in size and power to defend a Philippines state once the United States granted independence and withdrew the bulk of its own military force. A plan drawn up at the Army War College set a $25 million budget for the task, including pay, and that nearly caused Manuel Quezon, presumptive president of the impoverished nation-to-be, a heart attack. Frankly, the breadth of the task at hand in no way corresponded to any possibility of success without massive financial backing from the United States, which was very far along in robbing its own military of any possibility of defending the nation.

The effort expended by MacArthur, Ike (who was promoted lieutenant colonel in July 1936), and another aide sputtered along in a sort of hopeless vacuum. MacArthur’s grandiose plans were just plain unattainable and, to Ike’s mind, often quite absurd. As time went on, Ike came to detest MacArthur, whom he had never considered quite sane (though he did detect a sort of brilliance). The two nearly came to blows in late 1939 when MacArthur implied to Quezon that Ike had lied about something, when in fact the liar was MacArthur. That cut it; Ike was irreconcilably angry on top of being frustrated by what he perceived as having wasted years on an impossible mission. He requested an immediate return to the United States, which he would have had within a matter of months anyway. He sailed for home with his family in December 1939, by which time the world had been made topsy-turvy from the new war in Europe. He never suffered MacArthur’s company again.

Ike With the 15th Infantry Regiment

Lieutenant Colonel Eisenhower arrived in San Francisco with orders to report for duty with the 15th Infantry Regiment, a part of the 3rd Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington. While making a courtesy call on the commanding general of the Fourth Army, which was headquartered at the Presidio of San Francisco, Ike was instantly co-opted to work with the Fourth Army staff on urgent plans to accommodate a proposed call up of the National Guard in the region from Minnesota to the entire West Coast.

During the course of the planning exercise, Ike drove a hundred miles to watch the 15th Infantry take part in an amphibious exercise in Monterey Bay. While strolling along the landing beach, Ike came upon the Fourth Army commander, who was accompanied by Army Chief of Staff George Marshall. This was the second time Ike and Marshall had met. The first was in Washington, when Colonel Marshall had dropped by the Battle Monuments Commission offices to invite Major Eisenhower to join his staff at The Infantry School, an idea shot down by the chief of infantry. Upon a hurried introduction by the Fourth Army commander, Marshall quipped a knowing reference to Ike’s long service with MacArthur, whom Marshall also loathed: “Have you learned to tie your own shoes again since coming back, Eisenhower?” “Yes, sir,” Ike replied affably, “I am capable of that chore, anyhow.”

Ike finally reported in to the 15th Infantry in February 1940 at its temporary base at Fort Ord, California, just up the road from Monterey. He was assigned as regimental executive officer, but his request to command a paper infantry brigade was also granted when the 15th returned to Fort Lewis. The Army, under Marshall, was preparing for massive expansion, and it was already prospectively manning up skeletal cadres for future units and commands. By this stage of his career, the formerly obscure Ike was seen as something of a comer—had been since his sponsorship by Fox Conner, a distinction not lost on the sagacious Marshall.

Not beyond Ike’s ken, there was something like a bidding war going on for his services by corps and Army commanders everywhere in the United States, but the chief of infantry balked at each request; he wanted Ike to spend some time with the troops. Ike found himself in his element as the 15th Infantry spent most of the spring and summer of 1940 engaged in grueling exercises in the field, including a 1,100-mile vehicular road march planned mainly by Ike, who was never happier than when he exhausted himself in the field, with the troops.

Choosing Gerow Over Patton

In October, Ike received a letter from Patton, who wrote that he was to be given command of one of the new armored divisions. Would Ike like to command an armored regiment? Hell, yes!

But it was not to be. Another close friend opened a bid on Ike. Brig. Gen. Leonard “Gee” Gerow had been especially close to Ike since Lieutenant Eisenhower had reported in to the 19th Infantry at Fort Sam Houston in 1915. Four years Ike’s senior in grade but Ike’s age, Gerow was probably Ike’s best friend in the Army. The two had also attended the Command and General Staff School together. There, Gerow had been Ike’s study mate and closest competitor; he had come in number two behind Ike by two-thirds of a grade point. They had also been neighbors in Washington during overlapping tours. Now, in mid-November 1940, as Ike dreamed of commanding a tank regiment under his dashing pal, Patton, Gerow asked Ike to serve under him at the Army War Plans Division (WPD).

This was a moment of truth, a historical pivot point, actually. Accepting Patton’s offer, once he was released by unseen hands, stood a good chance of taking Ike to the summit of battlefield glory, for the unrestrainable Patton would certainly command men in battle. But Gerow’s offer was a path, not so much to glory, but to relevance, even if not to a paragraph in history books. Ike at 50 knew where the touchpoints and waystations of his career trajectory had been taking him after his tutoring by Fox Conner. If he cared about his Army and his nation as much as he hoped he cared, there was really only one offer he could take, and that was Gerow’s. But he hemmed and hawed in his long, written response to Gerow, leaving the decision to his friend.

The Army had other ideas. Before Gerow could act, the Army bureaucracy reassigned Ike to the General Staff Corps and then as chief of staff of the 3d Division, the 15th Infantry’s parent unit. He labored with the division until March 1941, when he received a temporary promotion to colonel and a posting as chief of staff for IX Corps, also headquartered at Fort Lewis. Among Ike’s varied and urgent duties with IX Corps was accommodation for several National Guard divisions and independent units based in the IX Corps area as well as upgrading facilities to house and train tens of thousands of conscripts called to duty under the Selective Service and Training Act of 1940.

Ike in the Third Army

In mid-June 1941, the Third Army commanding general wrote to Marshall to request a new chief of staff, and he named Ike as his first choice. Marshall immediately acceded and stamped the transfer request “urgent.” Ike reported to Third Army headquarters, in San Antonio, on July 1, and was assigned as deputy chief of staff. A month later he was named chief. This was all just in time to oversee the Army staff during the largest maneuvers ever held in the United States, mostly in Louisiana. Third Army (designated Red Army) won the mock war and Ike was given a huge amount of the credit. On September 29, 1941, Ike was promoted temporary brigadier general.

Third Army was still basking in its deserved glory, working hard to prepare for further expansion and field exercises, when the roof fell in on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines. On December 12, the day after Germany and Italy declared war, Ike received a phone call from Colonel Walter Bedell Smith, Marshall’s military secretary: “The chief says for you to hop a plane and get up here right away. Tell your boss that formal orders will come through later.” This, as it turned out, was The Call most senior military professionals only hope they’ll receive when their nation is at war.

Ike was on his way to catch a train to Washington within an hour of Beetle Smith’s phone call. In Washington early on the second Sunday of the war, he dropped his bag at brother Milton’s apartment and reported in to Gee Gerow, who was still running WPD. Gerow gave Ike a desk but there was no work yet. That depended on his meeting with Marshall.

The chief of staff summoned Ike to his office. It was the fifth time the two had laid eyes on one another, and the first time they ever exchanged more than two or three polite sentences. But they knew one another because they had shared the attention of Fox Conner, who had drilled into Ike’s head during the Panama sojourn that Marshall was a military genius. Conner had also commended Ike to Marshall. And that was good enough for both Conner devotees.

Briefed on the Pacific

The first order of business was bringing Ike up to date on the situation in the Pacific. Marshall gave a concise briefing, perhaps 20 minutes in length. The long and the short of it was that the Americans, British, and Dutch didn’t stand a chance of retaining their holdings west of the 180th meridian. Above all, the Philippines would have to be sacrificed in due course.

At the conclusion of his depressing brief, Marshall asked Ike, simply, “What should be our general line of action?”

This question was all Marshall. Ike realized he was being tested by the great man. Rather than blurt out an answer, he replied “Give me a few hours.”

Back at his desk, Ike ran everything he knew about the situation through his head. He was 51 years old then, had spent 30 years as cadet and soldier. He had as good a military education as any other new brigadier general—better, in fact, than most. Everything he was and everything he knew pointed to just one possible answer.

Comprehending that, per prewar analysis and policy—per War Plan Rainbow No. 5, which he might not even know about yet—it was plain to see that the Philippines could not be effectively resupplied or meaningfully reinforced ahead of defeat and surrender. If the Allied nations were ever to achieve a turnaround in the Pacific, it was an absolute necessity that Australia be preserved as a base from which the Allies could start back up the long road to victory. This is the answer he took back to Marshall—an answer accepted so quickly as to make it plain to Ike that he had confirmed Marshall’s own conclusion. This agreement fused a personal bond that never broke.

The Plan to Defend Australia

Ike became immersed and consumed in the preservation of Australia. He took the lead in planning. Every detail concerning Australia passed across his desk, often requiring his consideration and approval. So much of it tied into matters of supply that he met daily with Brig. Gen. Brehon Somervell, the War Department’s resident supply and procurement chief. Few people got on well with Somervell, but Ike certainly did, probably due to his intimate appreciation of Somervell’s job, stemming from his days in the assistant secretary of the war’s office. Ike’s relationship with the prickly Somervell turned out to be another critical alliance.

In a series of steps and at some great risk, the winter of 1941-1942 was consumed by the early but critical stage of turning Australia into MacArthur’s primary base in the western South Pacific. (MacArthur had been reactivated at three-star rank in mid 1941, appointed Far East commander, promoted to four-star rank as the Philippines defenses collapsed around him, and finally dispatched to Australia by presidential order.) There were other side efforts to build a last-ditch line of defense across much smaller islands in the western South Pacific—in other words, competition for critical supplies and a very small pool of adequately trained troops. Indeed, mostly half-trained units were dispatched in the hope, but by no means the certainty, that they could complete their training ahead of battle.

Operations Division Chief of the War Department

Though at this time Ike had little contact with planners assigned to the many conundrums attending America’s entry into the war in Europe, it turned out that transforming Australia into an offensive base was pretty much the same as transforming the British Isles into an offensive base. Ike missed out on meeting Sir Winston Churchill and a high-level British military delegation when they descended on the War Department in December for ARCADIA, but he was briefed and some of his opinions were sought. The British delegation left behind high-ranking officers to liase with the American chiefs of staff. The British Army representative was General Sir John Dill, who had recently been routinely superceded as chief of the Imperial General Staff. Dill was given open access to Marshall and WPD.

Ike succeeded Gerow as WPD chief on February 14, 1942. At that moment, plans were being wrought to transform the uniformed side of the War Department into a more efficient war footing. WPD was somewhat rejiggered and on March 9 redesignated Operations Division (OPD) of the War Department. Its mission was to serve as Marshall’s nerve center, his command post, his think tank for running the war. Under previous plans, before the United States became involved in the global war, it had been thought that the chief of staff would take to the field at the head of the fighting Army, leaving lower ranked deputies to run the Washington operation. The reality, post-Pearl Harbor, was that it would be all as formidable a leader and executive as Marshall could do to control the American war effort with his immense and growing staff in Washington. So, on March 9, 1942, Ike became the Army’s first OPD chief, with a jump in (temporary) grade to major general. That same day, some earlier informal reconfigurations became formalized. In one such move, the Army itself was divided into three major components: the Army Air Forces (AAF) under Lt. Gen. Hap Arnold, the Army Ground Forces (AGF) under Lt. Gen. Lesley McNair, and the Army Service Forces (ASF) under Lt. Gen. Brehon Somervell.

Effectively the overseer of every detail of the U.S. Army’s war effort, Ike was quickly brought up to speed and given a hand in literally everything. A lot of it seemed like background noise intended to drown Ike in minutia. His personal permission for Fourth Army to issue three thousand rifles to the Alaska Territorial Guard was a good example of a necessary but distracting intrusion on his time and thought processes.

Planning the Build-Up in Britain

Ike realized on March 10 that his superiors throughout the U.S. military were coming around to the idea—an idea he had been pushing—of an invasion of France from yet-to-be-built bases in Britain. But his flush of achievement died swiftly when news reached him at his desk that his father had died earlier in the day. Unable to get away to Kansas, Ike used hard work to displace his grief, but he was finally overwhelmed by his emotions. He quit work at 7:30 that evening. Later in the month, after thinking profoundly about the father-son relationship, he forced himself to take a weekend off with Mamie to visit John at West Point, which the young Eisenhower had entered the previous June.

As soon as Ike returned to his desk at the War Department, the whole world seemed to realign itself around him.

Marshall visited England in early April to brief British commanders on current American planning, show interest, and collect facts and impressions. Shortly after his return to Washington on April 17, the chief of staff called Ike in to lament about how little time he had been able to spend looking over the nascent American field and service commands there. Perhaps Ike would make an inspection tour of those commands; no doubt a major general would be less encumbered by the ceremonial sideshows a four-star general and Army chief of staff inevitably endured when visiting foreign nations. Ike asked only to be allowed to take with him Marshall’s own chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Mark Clark, a 1917 West Point graduate whose insights both Ike and Marshall had come to value over many years of shared service.

Ike’s Inspection Tour

It took until May 23 for Ike and Clark to set out. Hap Arnold joined them for the ride, as did the chief of naval aviation and a senior RAF staff officer based in Washington. They flew via the northern ferry route, from Maine to Newfoundland to Labrador to Greenland, to Iceland, to Scotland, and on down to England.

Tops on Ike’s list of visits was the one with Army Air Forces Maj. Gen. James Chaney, at the headquarters of U.S. Army Forces in the British Isles (USAFBI). Here, Ike sensed that Chaney and his staff were operating under some sort of malaise. They certainly did not seem charged up by their work. Ike noted disapprovingly that they all dressed in civilian clothes on weekends, a sure sign they were not a hundred percent into the effort workaholic Ike expected of all American soldiers in time of war. He also noted that the USAFBI staff had not been dealt a fair hand by higher headquarters. Clearly it had not been kept in the planning or information loops to the degree USAFBI required to effectively facilitate the rapid-fire changes taking place in the British Isles, not to mention a sufficient familiarity with events worldwide that might impinge on events in northwestern Europe.

The inspection tour was comprehensive, a serious effort by two extremely serious men to get a grip on events, organizations, and personalities. Among the many British officers Ike met for the first time was Lt. Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery, who briefed the Americans on a large training exercise he was overseeing. Another notable British officer Ike met with was Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, cousin to King George VI and commander of Britain’s special operations—commando—forces.

Conclusions of the Trip

Ike personally reported his findings to Marshall on June 3. His bottom-line recommendation with respect to USAFBI was that Chaney be replaced without prejudice by a current War Department insider who had a complete, up-to-date picture of the war effort. Marshall asked if Ike had an individual in mind. Of course he did. His first choice would be Maj. Gen. Joseph McNarney, an airman serving as Marshall’s own deputy chief of staff. (McNarney happened to be Ike’s West Point classmate.) Ike’s reasoning was sound; it would be a long time before there were significant Army ground forces deployed to the British Isles, and much longer still before they were sent to battle. In the interim, the war would be taken to German-occupied Europe and Germany itself by American airmen. Marshall demurred; his own deputy chief was too essential to be spared, and he also felt strongly that he required an airman as his deputy. Ike asked to be given time to think about another recommendation. Unbidden, Ike recommended that Clark be returned to England as commanding general of the II Corps headquarters, which was about to be formally shifted to England to take part the invasion.

Ike had also devoted much time in England to assessing BOLERO, the operation to supply the proposed invasion with all the men and stuff it would take to cross into France and ultimately drive into Germany. Things had not been going well for some time; everything that could be put into the pipeline at the North American end was moving into place in the British Isles far too slowly, if at all. There were profound problems at both ends of the pipeline, and along the way. On June 6, Ike recommended that a lieutenant general charged with unsnarling BOLERO be dispatched to England as soon as possible.

Beginning with a blank piece of paper, Ike also had gone to work after his return from Britain on a comprehensive framework for a U.S. Army command structure to oversee the eventual air war to be run out of England and the general build-up of all American forces—air, ground, perhaps even naval—in the British Isles. On June 8, 1942, Ike presented Marshall with a paper entitled “Directive for the Commanding General, European Theater of Operations.” This posited a joint command, with a single commander in chief, for all American forces deployed to Europe.

When Ike presented his paper to Marshall, he admonished the chief of staff to give it his full attention as soon as possible. Marshall replied, “I certainly do want to read it. You may be the man who executes it. If that’s the case, when can you leave?”

ETOUSA Commander in Chief

On June 11, Marshall told Ike he would indeed be “the man who executes it.” Also, per Ike’s recommendation, Marshall assented to Mark Clark being sent back to England as commanding general of the II Corps.

Only then did Ike begin to consider that every task he had undertaken in Washington, since being summoned to WPD, had been monitored by Marshall as a proof toward this singular order to command, this singular demonstration of trust. The Army had long supposed that the chief of staff would command the armies in the field. Real-world exigencies had led to the appointment of one man to stand in the chief’s place, and that one man—if he proved to be up to the job—was Dwight David Eisenhower of Abilene, Kansas, and no other. Marshall conferred a third star on Ike. Though he remained a substantive lieutenant colonel, Ike had thus been elevated over the heads of more than 300 more senior major generals.

Ike’s first act as ETOUSA commander in chief was to appoint Mark Clark as his deputy. (Clark continued to command the II Corps, which had no troops to oversee.) Marshall promoted the hard-nosed Beetle Smith to brigadier general and appointed him Ike’s chief of staff. Smith would control access to Ike as he had to Marshall, and not so much of it as to distract the theater commander from the heart and soul of his mission.

Ike also met with many Washington luminaries whose various blessings he needed or would need. Not for the first time, he paid a courtesy call on President Roosevelt, who happened once again to be hosting Prime Minister Churchill. Secretary of War Stimson, a hell-for-leather type, urged Ike to launch the invasion of France at the earliest opportunity.

A stop at the Chief of Naval Operations offices yielded an important discussion with Admiral Ernest King pertaining to Army-Navy cooperation in the ETO. Long, long tradition guided the relationship between the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy from the perspective of “paramount interest”—who really owned the operation anyway? At very little urging, and in spite of an intense Atlantic-wide antisubmarine campaign then underway, King allowed as the invasion of northwestern Europe—an objective to which all American and British effort aspired—was the Army’s prime responsibility no matter how much the Navy bolstered it. Capping the discussion, the typically prickly King invited Ike to communicate directly with him as and when he found the need.

Eisenhower’s Trusted Officers

Lieutenant General Eisenhower returned to England on June 24. For the moment his brief as ETOUSA commander in chief registered only upon the thin roster of U.S. Army units and personnel in Europe. Ike was under particular orders from Marshall to integrate under direct Eighth Air Force control all AAF personnel then in the British Isles, including a panel of special observers assigned to the RAF. Marshall had also ordered Ike to direct the Eighth Air Force, in broad terms, to aim at attaining total air supremacy over northern Europe before the expected invasion of France was launched across the English Channel. This last was a mission that never went away until Germany lay in ruins and utterly defeated. Ike formally assumed his new command on June 25, 1942.

Almost unnoticed and uncommented on during the period of the changeover, Maj. Gen. James Chaney returned to the United States on June 20 to resume command of First Air Force, which he had himself established in December 1940. Chaney never recovered from his fight with Arnold over the USAFBI air command structure. At war’s end, Chaney, still a major general, was the island commander at Iwo Jima.

Ike went straight to work as soon as he could settle with his staff into their headquarters, a large apartment building near Grosvenor Square that had been commandeered entirely for ETOUSA’s use. Ike disliked being in the center of town but acknowledged that a scarcity of transportation and the need to attend meetings in many nearby buildings made it impossible to relocate to the country. He nevertheless planned to move to the country as soon as vehicles and prefabricated buildings could be shipped from the States and a suitable site could be found.

An early courtesy call was made by Admiral Harold Stark, the former chief of naval operations, now the head of U.S. Naval Forces, Europe. Stark put the younger flag officer at ease, explaining that “the only real reason for the existence of my office is to assist the United States fighting forces in Europe. You may call on me at any hour, day or night, for anything you wish. And when you do, call me ‘Betty,” a nickname I always had in the service.” Soon after this reassuring encounter, Ike was joined by a fellow Kansan, his senior naval subordinate and amphibious force commander-designate, Rear Admiral Andrew Bennett. There was little for Bennett and his naval subordinates to do yet, but the naval contingent would soon be engaged to the hilt preparing the largest, most complex amphibious assault in history. (America’s first amphibious assault of the 20th century, at Guadalcanal, would not take place for more than a month after Ike’s arrival in London. Until then, there were literally no “lessons learned” files for Bennett’s team to study.)

Ike relied heavily on Mark Clark, who filled in as ad hoc chief of staff pending Beetle Smith’s scheduled arrival in early September. Clark, in his capacity as II Corps commanding general, sought out suitable training areas in the English countryside. With Ike’s concurrence, the Salisbury Plain was selected and the II Corps command post was established nearby.

For the moment, and for a long time to come, Ike’s most important subordinate (and yet another fellow Kansan) was Maj. Gen. John C.H. Lee, a logistician, former infantry division commander, and holdover from the Chaney staff, now head, the ETOUSA Services of Supply (SOS). In addition to providing ETOUSA’s administrative backbone, Lee’s troops built and manned as needed literally everything ETOUSA required in the way of buildings, dumps, repair facilities, training areas, cantonments, and airfields. Whatever the British had done and would do to accommodate the Americans, Lee’s men and women turned it into something better. Lee himself would remain at Ike’s side throughout the war.

The Great Buildup

The AAF contingent in the British Isles was about to grow immensely as Ike settled in. The air organization was set up to look after itself in nearly all particulars, but it was subordinate to ETOUSA. Ike’s point of contact with the AAF community was Maj. Gen. Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, who had arrived in England just ahead of Ike. The two hit it off immediately even though Spaatz, like Lee, was Ike’s senior in age and had long been his senior in rank. Like Lee, Spaatz never left Ike’s side during the war against Germany.

Considering that Ike estimated that his command on English soil, before the armies moved off to France, would top two million Americans, there was really very little on hand to work with when Ike arrived. But plenty was on the way for one of the largest military buildups in history. For all that, though, only two American combat divisions were yet training on British soil and most of the AAF troops as yet were non-airmen in service and support billets doing advance work to support what was already scheduled to become the largest air organization ever devised and the world’s first and for two years its only strategic air force.

The peoples of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland had lived nearly three years awaiting the tangible reality of a world-class ally—this world-class ally—to help them right the wrongs of Fascism and Nazism. Even the small advance phalanxes, when they arrived, made the peoples of the British Isles swoon with relief. Shortly, though, the British would simply be swamped by a tidal wave of richness of spirit and goodwill bubbling over the Americans’ richness in material wealth. Soon they would not quite fathom what hit them. And later, the Nazi thugs across the Channel would not know what hit them either.

It was Ike’s job to modulate American, British, and Canadian forces to undertake one of the most difficult military challenges in all of history. To do that, he understood that he, a man from the geographic center of a continent-size nation, had somehow to modulate the three cultures while completely surrounded by one of them. From his first day as America’s top soldier in the British Isles, he could not wait to get started.

Ike was as much a diplomat as a military leader. Few Generals could have melded together a diverse group of allies with their individual interests as Eisenhower. His handling of relationships with De Gaulle and Montgomery were particularly telling. Through it all he managed to keep his well known temper in check in order to maintain a sense of unity among the military allies.